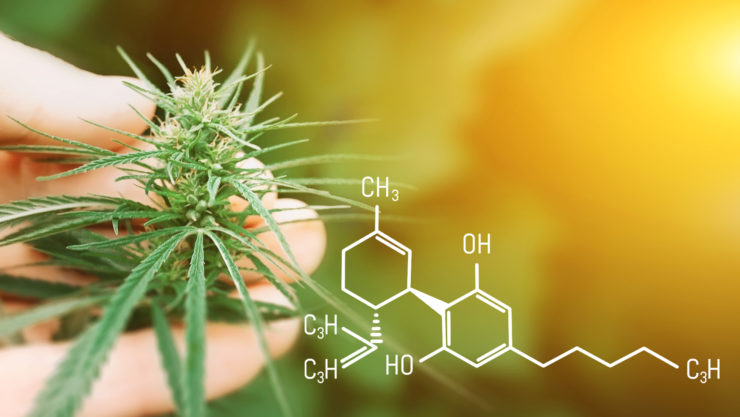

Hemp was legalized federally just over a year ago. During the run-up, legislators from Mitch McConnell to Ron Wyden said things like “[b]y removing hemp from the federal list of controlled substances, farmers can explore the bright future of this versatile crop, found in everything from a coffee mug to your car dashboard.” One planting season in, however, farmers aren’t doing so much “exploring” with respect to hemp: instead, the Brightfield Group estimates that 87% of 2019 hemp acreage was planted for CBD extraction. Among the many hemp farmers our law firm represents in Oregon, Washington and California, that number feels closer to 100%.

Will people get rich farming hemp for CBD? It’s hard to say, given the newness of that market, apparent oversupply issues and pricing volatility for CBD. Assuming long-term and robust demand for CBD products, though, it’s likely that large family farms will eventually dominate output, just as in U.S. agriculture generally. It also seems likely that the margins for these large farms will expand and contract similarly to margins for other crops, based on many complex factors. Today’s small hemp-CBD start-ups growing from 1 to 99 acres will likely diminish in profitability and prevalence.

And that’s where genetics come in. If hemp is to be like other crops, it seems probable that the truly big money will not be in hemp production, but in the creation and licensing of proprietary plant material. Along those lines, Oregon’s biggest hemp company already is a seed company called Oregon CBD. That oufit is approaching $1 billion in annual revenues after just a few short years in operation.

If you want a certain CBD-rich strain–or a CBG strain, or a CBN strain, or any other kind of hemp strain–you would go to a seed company. You would do this even though seed certification is not addressed under the 2018 Farm Bill because you want to be sure that you get females and those females do not germinate into 0.3%+ THC plants. You would do this because you want proven genetics and you want warranties around those genetics. And eventually, you would do this because you want to be sure your hemp seeds are designed for production with certain types of herbicides in mind, a la Roundup Ready corn.

The federal regulatory environment is shaping up to facilitate success for firms with valuable hemp genetics. Currently, hemp genetics firms are able to formally register and protect their intellectual property, design products with specified epigenetic factors in mind (i.e. approved pesticides), and count on clear federal parameters for their business models. Some of these are helpful, others less so. Each crucial plank is briefly summarized below.

- Intellectual Property. Earlier this year, USDA’s Plant Variety Protection Office (PVPO) began accepting applications of seed-propagated hemp for protection under the Plant Variety Protection Act. PVPO examines new applications and grants certificates that protect varieties for 20 years. Elsewhere, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) already has granted its first hemp plant patent, with more in the pipeline. Plant patents afford similar protections to protected plant varieties with respect to duration and scope. (For a good explanation of the interplay and differences between plant variety and patent protection for plants, go here.)

- Epigenetics. Last month, the Environmental Protection Agency approved a list of ten pesticides to be used in hemp production. This means that firms creating and registering hemp plant media will have crucial guidelines for seed design. It seems very likely that hemp strains eventually will be built with the application of certain chemical agents in mind, again like Roundup Read corn, if this type of research and development is not underway already.

- Crop Insurance. The USDA’s Risk Management Agency (RMA) recently announced a pilot insurance program for hemp growers. Farmers will now have greater incentive to grow hemp at scale and to innovate, which, in turn, means a more lucrative and dependable market for seed genetics firms. In the bigger picture, the USDA itself will also encourage cultivation by providing a federal plan for producers in states or tribal territories without their own USDA-approved plans.

- Crop Testing Rules. The problematic total THC testing protocol in USDA’s final interim rule will create demand for innovation in genetics– unless we see major changes following the close of public comment on January 29. But wherever we end up, seed firms will strive to create and refine cultivars that: a) express certain cannabinoids predominantly and b) pass testing strictures. It has already been argued, for example, that the current testing rules could eliminate the viability of current CBD strains altogether. Time to innovate.

In all, some farmers will do well growing hemp, particularly the larger family farms. Others will inevitably fail. But the big money will be made in plant genetics, including the design, sale and licensing of intellectual property. As certain hemp cultivars move to the fore, the next few years will be crucial. And the owners of those cultivars stand to profit handsomely.